A Modern City in East Midtown?

By ROBERT A. M. STERN

Published: April 21, 2013

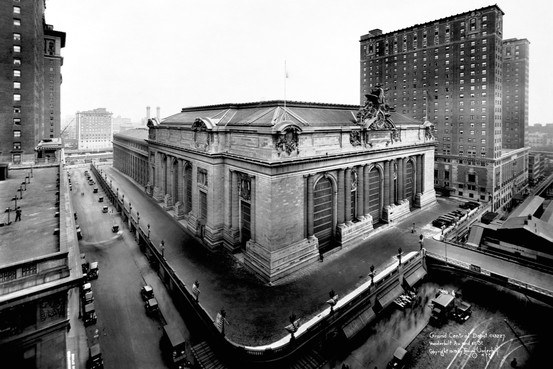

Last summer the Department of City Planning released its East Midtown study, envisioning a taller, denser, shinier future for the neighborhood around Grand Central. New and more liberal regulations that will allow bigger office towers are on their way to the City Council for approval before the end of Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg’s current term. But what is a modern city, exactly? And is New York really in danger of falling behind new global cities like Shanghai?

With district improvement bonuses, the City Planning study proposes to double the developable floor area on some sites around Grand Central, allowing enough additional square footage to give us a neighborhood of towering office buildings, some as tall as 1,300 feet or more. (For reference, the Chrysler Building is 1,046 feet to the top of its spire.)

I’m nearly always an advocate of density: it’s socially beneficial and environmentally responsible. And I like tall buildings as much as the next architect, especially if I’m asked to design them.

But the advantages of density can go only so far without the infrastructure to support it. And the appropriateness of tall buildings is a question of where and when, and what they contribute to the public realm. Let’s all admit that the Pan Am Building, now MetLife, was a mistake in 1963, and is still a mistake from an urbanistic point of view. It disrupted the vista down Park Avenue that had become an essential part of our city.

Are we preparing to make the same mistake again, on multiple sites? The rezoning study makes no mention of protected-view corridors. Can we guarantee that in the future the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building will not be lost in thickets of taller buildings?

And what of our streets and subway platforms? I commute through Grand Central several times a week, and at 6:20 a.m., when I catch my train to New Haven, the terminal is already full of people. When I return at 6:30 or 7 p.m., I can hardly make my way to the stairways and escalators that lead to the Lexington Avenue subway platforms.

How will the added workers quartered in these new buildings get from their trains to their desks? The plan says that special assessments and payments in lieu of taxes will guarantee “pedestrian network improvements as development occurs.” There is nothing wrong with privately financed infrastructure improvements. But the study, if I read it correctly, gets it backward: first you put in the infrastructure, then you build the buildings. Look at the example of Grand Central, the private enterprise that spurred all this development in the first place.

What lessons should we take from other great cities? In the early 1990s, Shanghai organized a special economic zone that led to the development of a financial hub in Pudong, on land previously occupied by warehouses and wharves. Towers sprouted to create an instant iconic skyline, but with a regrettable, scaleless urban moonscape below.

Should we in New York in 2013 emulate the Shanghai of the 1990s? Or should we heed the lesson the Chinese themselves have subsequently learned, that saving old buildings and neighborhoods is essential to the continued vitality of great cities? In Shanghai, the pre-World War II buildings along the Bund, which loom so very large in the city’s appeal, have been saved and repurposed. Nearby, at Xintiandi, a historic residential neighborhood of stone houses and tight alleys has been transformed into a chic, walkable retail and entertainment district.

Terminal City, a sophisticated mix of hotels, clubs, office buildings and residential blocks at the heart of East Midtown, was built on platforms bridging the rail yards north of Grand Central. It was a bold plan to create valuable real estate where once there had been urban blight. As much as anything, this development created what the world knows today as Midtown Manhattan.

Some judicious pruning is no doubt appropriate, but are the right areas being targeted? In the center of the study’s bull’s-eye diagram are buildings worth preserving: George B. Post’s Roosevelt Hotel, the Yale Club by James Gamble Rogers, Carrère & Hastings’s historically important Liggett Building and Arthur Loomis Harmon’s extraordinary Shelton Club Hotel, now a Marriott, which inspired artists like Georgia O’Keeffe to some of their best work.

Those and other distinguished buildings have come to define the area around Grand Central, but are not yet official landmarks. Instead of blindly targeting what is oldest for replacement, as the study does, why not develop a thoughtful preservation plan that takes a broad look at what is worth saving?

In fact, the best path toward ensuring the future of East Midtown may well be that of preservation. Preservation, which too many in the real estate community reflexively oppose, has been a better stimulant for development than rezoning. SoHo and the Flatiron district were two of the most moribund parts of the city in the 1960s and ’70s; once they were designated as historic districts, the fortunes that poured in made them more vital than ever.

We can do the same in East Midtown. The historic hotels and older office buildings of Terminal City could be repurposed for residential uses (and, I might add, the Yale Club is doing just fine). Some of these older buildings, their futures uncertain, may look a little dowdy today, but I’m confident that the stability that landmark designation provides would lead owners and developers to rediscover their intrinsic value.

Our diversity, and the fact that we don’t look like Pudong, is the reason many creative types choose New York over the bland banalities of Silicon Valley, just as in London, they’ve chosen Clerkenwell over Canary Wharf, and in Paris, just about anywhere over La Défense.

Why do tourists flock here? Because we are what we are. As we go forward, we need to evolve, not copy someplace else. We can’t sacrifice our legacy for the benefit of a small group of property owners, especially when other, less controversial sites, with the potential for visionary large-scale urbanism on par with the potential that Terminal City seized 100 years ago, are gaining momentum.

At its most fundamental level, the problem with the so-called planning study is that it’s not a plan. It trusts that developers will build world-class buildings, and that we’ll sort out the public realm as we go. It looks to improve East Midtown by adding world-class office stock, but it dices the neighborhood into independent development zones with little broader thinking.

There’s nothing of the unified vision that gave us Rockefeller Center, with its iconic Channel Gardens, its world-famous ice rink and its shop-lined indoor passageways that connect office buildings to subways. The proposed East Midtown up-zoning doesn’t give anything back to New York. It’s all about real estate and not about place-making, or should I say, place-saving.

Even with 80 percent of its building stock over 50 years old, East Midtown is today, in the words of the planning study, “the best business address in the world.” Let’s keep it that way.

Robert A. M. Stern, architect, is dean of the Yale School of Architecture and a co-author of a series of books about architecture and urbanism in New York.