Two architecture students have an ambitious plan for North Brother Island, an abandoned, overgrown patch of green in the East River — they’d like to build a school for children with autism there.

Famous for its quarantine hospital where “Typhoid Mary” was confined in 1907, North Brother Island was closed to the public in 1963 after a juvenile drug rehabilitation center was shuttered.

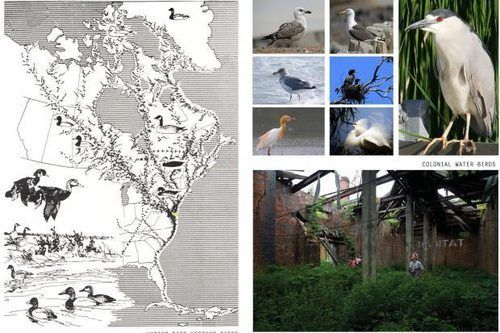

It’s now a protected bird sanctuary, but illegal visitors and aggressively growing vines are hurting the breeding grounds of colonial water birds during nesting season, explained Ian Ellis, who developed the school proposal with Frances Peterson while at the University of Texas at Austin’s School of Architecture.

They were charged with planning something that would be a topic of controversy, Ellis said.

“In its current state, North Brother is without the attention, improvements and upkeep it needs in order to continue acting as a habitat for the wildlife there,” he explained in an email.

The Centers for Disease Control estimates that one in 88 children in the U.S. is diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. The Bronx has the most underserved population in New York City for children with ASD, according to Peterson’s research.

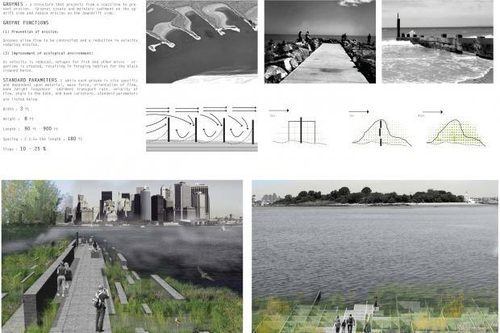

The designers dreamed of a school that would re-use five existing structures for potentially 208 students and 52 instructors, who would travel to the island via ferry. Their commute would take 10 minutes from Barretto Point Park and Soundview Park, but piers would need to be built.

The classes would be based around three gardens, “each providing a different degree of safety, exploration or risk in order to best satisfy the needs of students,” Ellis explained.

The proposal would also rehabilitate buildings that could be used as field offices for the Parks Department, Cornell University’s department of ornithology and the Audubon Society.

Four other structures would be left to decay naturally.

The aspects that make it appealing to birds — isolation, natural environments and refuge — also make it appealing for autistic children, Ellis said.

“It’s a sanctuary as it is. The school simply allows it to be one that promotes and nurtures the lives of children as well as the wildlife that relies on the island for nesting, foraging and reproducing,” he said.

Designing a school for children with ASD can be a challenge, according to Lisa Goring of the national advocacy group Autism Speaks.

“Each student’s needs can vary pretty broadly,” she said. “What may be appropriate for one student may not be appropriate for another. There is a need for a continuum of services and different types of programs.”

Advocacy groups have raised awareness about the dangers of children with autism wandering, especially close to bodies of water — something the architects discussed and tried to account for through “transitional spaces” connecting classrooms and gardens.

Ellis and Peterson haven’t estimated how much such a project would cost, though recognize it would be quite “an undertaking.”

“We still need to collaborate further with not only the agencies we propose to inhabit the island, but also with other specialists in seeing what developing a project like this would really entail,” Ellis said.

They haven’t had a chance to visit the island — yet.

Ellis, who finished architecture school last year and now works for an Austin-based architecture firm, is planning a New York visit this month.

“I hope to continue my research while there and, if I’m lucky, get to see the island in the snow,” he said.