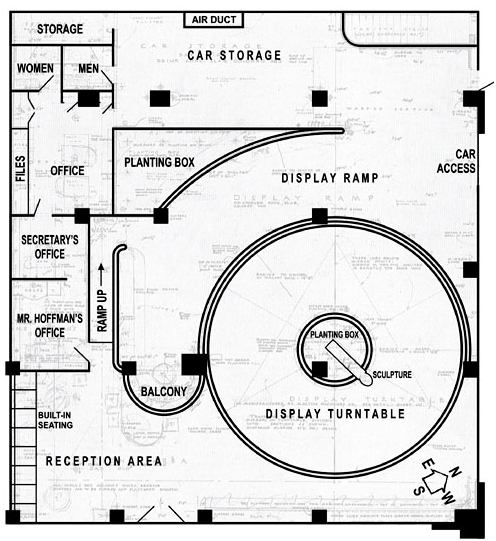

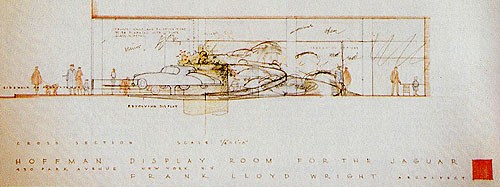

For six decades, Hoffman Auto Showroom, a luxury-car showroom with a distinctive swooping ramp stood at the corner of Park Avenue and 56th Street. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, it was the first of only three New York projects by the modernist master.

In six days late last month, the dealership was destroyed.

“The loss of a Frank Lloyd Wright, it’s a national tragedy,” said Simeon Bankoff, director of the Historic Districts Council. Like so many in New York, he had no idea the space was even gone.

The end came suddenly and unexpectedly. On March 22, the Landmarks Preservation Commission called the owners of 430 Park Ave. to tell them the city was considering designating the Wright showroom—until January, the longtime home to Mercedes of Manhattan—as the city’s 115th interior landmark. Three days later, the commission followed up with a letter. Both went unanswered.

Instead, on March 28, the building’s owners, Midwood Investment & Management and Oestreicher Properties, reached out to another city agency, the Department of Buildings, requesting a demolition permit for the Wright showroom. The permit was approved the same day, sealing the showroom’s fate.

By the following week, workers had arrived and removed every last trace of a space that some architectural historians say inspired Wright’s most celebrated New York work, the Guggenheim Museum.

The city has lost an architectural gem, albeit a small and seldom-noticed one. Almost no one saw it go. Even if they had, there is almost nothing that could have been done to stop it.

And yet this quiet disappearance also raises the question of whether there was anything worth saving. “I’m surprised, but I’m not,” said David Hoffman, an executive managing director at brokerage Cassidy Turley, who arranged Mercedes-Benz’s last lease for the space, in 2001. “It was notable solely because it was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, but it wasn’t the Guggenheim; it wasn’t monumental.”

Ironically, it was the Landmarks Commission’s good intentions, and a disconnect between it and the Department of Buildings, that doomed the dealership.

In August, the commission received a request to consider landmarking the showroom from Docomomo Tri-State, a preservation group focused on modernist buildings, and the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy. The commission decided to wait until Mercedes vacated the space to proceed.

Part of the reason was that an interior-landmark designation can be granted only to a public space, and there had been a long-running debate in the preservation community about whether the showroom was actually anything but private property. Also, the commission had little reason to believe Midwood and Oestreicher would take the action they did. The delay proved fatal, but the outcome was likely inevitable.

The commission is loath to designate a landmark without the owner’s support, because the landlord, not the city, is ultimately the steward of the space. In the case of the auto dealership, the steward simply had other plans.

Representatives for both Midwood and Oestreicher declined requests for comment.

“Regrettably, the showroom was dismantled before the formal public designation process could begin,” a commission spokeswoman said. “It is disappointing that the owners in this case demonstrated a disregard for the process.”

That process, however, is famously cumbersome. The commission cannot “calendar” a property—the first step in the landmarking process, and the point at which the Department of Buildings is notified not to allow work to be done on the potential landmark—until Landmarks has done sufficient research, which typically involves outreach to the owner. In the interim, the landlord is free to request demolition permits, and there is almost nothing either city agency can do to stop them.

The Wright showroom is just one of several such cases in recent years.

Back when the Madison Square North Historic District was proposed in 2000, the owners of the former ASPCA headquarters at 50 Madison Ave. removed much of the building’s Beaux Arts ornamentation, with the Department of Buildings’ blessing. The owners had plans for a multistory addition to create a luxury apartment building, and they did not want their work to be subject to the commission’s whims. The tactic worked, and the property was left out of the district. Taking a different tack, the Institute of International Education closed a conference center designed by Finnish architect Alvar Aalto in 2008, thus creating a private space exempt from landmarking.

Motivations for doing such end runs around landmarking are clear.

“I can’t think of too many owners that would be grateful to receive a phone call from the Landmarks Commission when they’re about to do work on a building, which could stop their ability to make that investment and increase the value of the building,” said Stephen Spinola, president of the powerful Real Estate Board of New York.

In the case of the Wright showroom, the architect who worked on the demolition permits corroborates the city’s timeline of the destruction coming shortly after the commission had reached out to the landlords. Silviu Zahara, of architecture firm Belea Group, said he had received the job two weeks ago, but he also insists he had no idea the space was crafted by one of the nation’s most revered designers. “The drawings I got were from an architect I’d never heard of,” he said. “Actually, it wasn’t a great-looking space.”

To be sure, this was one of Wright’s lesser works. Mr. Bankoff of the Historic Districts Council said that when he mentioned it to certain in-the-know colleagues, they were shocked to learn there was a Wright hiding in plain sight on Park Avenue.

Even the renowned architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable was lukewarm on the showroom. “The spiral ramp motif … which was to be so beautiful an element in the Guggenheim, is employed here, though far less effectively, in part because of the low ceiling and partly because the cramped, abrupt turning motion all too clearly recalls the ramps of multifloor parking garages,” she wrote in a 1966 book.

“It’s outside our scope as an institution, so we don’t know what to do about [the demolition], but it’s pretty bad,” said Richard Armstrong, director of the Guggenheim.

Some question whether there was any Wright worth saving, since the space was renovated twice, first in the 1980s and again in 2001. The merits of the space would have been considered at the Landmarks Commission.

“That’s a debate we should have had, and could have had, but now we can’t” because of the demolition, said Vin Cipolla, president of the Municipal Art Society. “That’s what the landmarking process is for.”

Margery Perlmutter, a member of the Landmarks Commission, was shocked to learn about the loss of the showroom.

“All it takes is a savvy landlord and a smart tenant to do something special with that space,” she said. “How many boutiques can claim to be inside a Frank Lloyd Wright? None that I know of, unless you count the Guggenheim gift shop.”

Just how much of an asset the space’s pedigree could have been to a retailer will now never be known. But Faith Hope Consolo, a retail broker at Douglas Elliman and a self-professed fan of Wright, has her doubts.

“It means nothing to a new retailer; they couldn’t care less,” she said. Instead, she estimates that having a blank slate to work with could add hundreds of dollars per square foot to the value of the lease, especially given the location, a block off busy 57th Street.

“Of course, under the law the landlords had the right to do this,” Ms. Consolo said. “I just wish they’d had the same respect for Frank Lloyd Wright as they did for their own rights.”