Kerri Jacobs reports for Metropolis Magazine

DUMBO Principle

A Brooklyn developer asks for more height in exchange for a livelier public realm. A good deal?

Karrie Jacobs

Courtesy SHOP

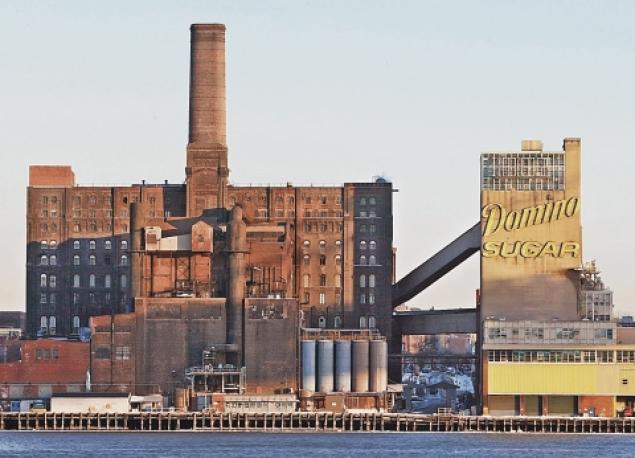

The renderings were pure eye candy, made for tweeting and retweeting. They showed a dazzling quartet of new buildings flanking the landmark Domino Sugar plant on the Brooklyn waterfront. Three of the towers were loop-shaped, reminiscent of OMA’s Beijing CCTV building, causing New York magazine’s Justin Davidson to joke that the development could be read as the word “OOOH.” Almost immediately some Internet wag doctored the renderings so that the buildings spelled out the name of the architecture firm that dreamed them up: SHoP.

But, in truth, the renderings didn’t show buildable architecture. The buildings were placeholders for ones to be designed later, and the image was an attention-getting ad for a master plan. What the renderings actually showed were outsize symbols of the developer’s intention to build a porous neighborhood—one that doesn’t form a wall between the East River and the rest of Williamsburg.

What you couldn’t easily glean from those computer-generated portrayals of a proposed place, or the 140-character missives that accompanied them, was that the most radical aspect of the project wasn’t its engineered cut-outs but the attitude of the development team led by Jed Walentas, son of David Walentas, the man who invented the Brooklyn neighborhood of DUMBO. Radical isn’t even the right word because what Walentas the Younger intends is a full-scale build-out of his family’s decidedly hands-on, curatorial—and oddly medieval—approach to urbanism.

The story of Walentas the Elder is mostly a study in patient, determined adaptive reuse: He bought most of DUMBO, 13 run-down industrial buildings tucked between the east ends of the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges, for $12 million in 1979. He thought the area was a logical spot for the city to put its back-office functions, but soon discovered that zoning wouldn’t permit it. Instead, he waited, allowing the disused manufacturing buildings to fill up with artists and amass cachet until he was finally able to get his holdings rezoned in the late 1990s.

Since then it’s been a mixture of high-end residential spaces, pricey condos and rentals, and offices for creative businesses, with a handful of artists still in the mix.

But, as DUMBO became more conventional, Walentas the Younger began seeding it with unique retailers, attracting them with subsidized rents. The renowned confectioner Jacques Torres began his chocolate empire in a subsidized shop in DUMBO. The Walentases gave a home to Melville House, a publisher specializing in literary novellas, and Galapagos, a performance space priced out of Williamsburg. They’ve handcrafted a little upscale village, one that’s still interesting and somewhat unpredictable, a testament to the power of enlightened self-interest.

Then, last summer the Walentases’ company, Two Trees, bought the Domino site from its previous developer, CPC Resources, for $185 million. Jed Walentas quickly signed up SHoP to rethink the site plan, originally done by Rafael Vinõly, which called for 2,200 apartments in four new towers and also in the former sugar refinery.

Instead of using CPC’s plan, approved by the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Process (ULURP) after a long six-year ordeal, Two Trees decided to restructure the site and go through the approval process all over again. “I don’t know the last time in the history of the city this has happened,” says SHoP principal and Columbia University professor of real estate Vishaan Chakrabarti. “

Jed came to us and said, ‘You know, we just want a better plan, even if we have to go through ULURP again.’” Chakrabarti called this a “masochistic challenge.” Walentas, for his part, says, “I think the process is helpful. The fact that we’re doing it to some degree voluntarily explains why there’s so much widespread support for this project.”

So there was Jed Walentas one brisk March evening at a south Williamsburg bar called the Woods, standing before a full house of beer-drinking hipsters explaining his philosophy of urbanism. It was the first public meeting about the project since the release of the new plan. Walentas, wearing a zippered hoodie over a button-down shirt, was a curiously uncharismatic figure; he came across as a kind of slacker Jimmy Stewart.

Oddly, the fact that he appeared incapable of delivering the polished spiel one expects from a developer worked in his favor. “We will occupy ground-floor spaces with small neighborhood retail,” he said. “It will not be big box. It will not be Starbucks. It will not be Duane Reade.” He added, “What we can achieve is a project that is socially contextual.”

I sipped my beer and recalled all the times I’ve said the city should offer some sort of incentive to developers—similar to a plaza bonus—for giving preference to local merchants in ground-floor retail. I’d never understood why every new building seemed to have the same stores until a conversation earlier that day. “The reason for that is the bankers,” Chakrabarti informed me. “Those chain stores are ‘credit tenants.’”

In other words, having a Duane Reade in the building reassures the bank that’s holding the paper on a project. Two Trees, on the other hand, is not dependent on the banks for its financing, and Jed Walentas argues, “There’s a real public benefit to being well-enough capitalized to take a long-term approach.” Further, he believes that developers should “make some sacrifices” to improve the character of a neighborhood.

Sacrifices? What New York City developer has ever sacrificed anything? But because Two Trees is largely self-financed, its approach to development can be idiosyncratic. So what’s radical isn’t the way the proposed buildings look on the skyline, it’s what happening at street level. Watching Walentas the Younger in front of the Williamsburg crowd, it was tempting to write him off as naïve, as a kid who doesn’t know what he’s talking about. But he’s 38 now and an experienced developer.

While his father’s ownership of an entire neighborhood can be seen as an accident of history, Jed brings with him a degree of intentionality. His dad is the adaptive reuse guy, but Jed is the Walentas who builds: The firm’s apartment buildings on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn, and its Mercedes House—a twisty thing designed by Enrique Norten on the western fringe of midtown Manhattan—those are Jed’s babies. He also recently helped develop Williamsburg’s Wythe Hotel, a former barrel factory topped with a glass-and-steel addition. But the Domino site is huge. It’s his answer to DUMBO, his magnum opus, an opportunity to play god with three million square feet on 11 acres.

Note that Two Trees wants what New York City developers invariably want—permission to build taller: 60-story towers instead of 30 stories. The company claims that the added height is a public benefit, the key to the plan’s “porosity.” Tall and skinny, in other words, is better than short and wide. And maybe it is.

Because they’ve changed the composition of the project, reducing the number of residential units slightly (116 fewer), and adding more than a half-million square feet of office space and extra acres of open space (the waterfront park will be designed by James Corner Field Operations of High Line fame); they argue that they need the added height to insure the proper return on their investment.

Renting out office space is less lucrative than renting out apartments. (One can only sacrifice so much.) But the offices are essential, because, Chakrabarti says, “Jed believes that the secret sauce in DUMBO is the office worker. They’re what makes the retail and the bars work and what makes it a lively neighborhood.” He also contends that the offices will reduce the development’s load on the already overburdened subway system because some workers will reverse commute and others will live in an adjacent tower. Again, maybe so. And maybe the East River Ferry will come to the rescue.

There are always good arguments against building three million square feet of anything anywhere. As one woman in the crowd called out: “Why do you need to build so much?”

I wanted Jed Walentas to answer honestly: “I’m a developer, lady. I build, therefore I am.” But instead, he just went on talking about the qualities he says will make the project “socially contextual.” And he almost lost me. But then someone else asked him: “How do you know?” I liked his reply: “We don’t have a marketing strategy,” he told them. “We don’t have fancy spreadsheets to demonstrate this.” Call it the DUMBO principle.

In an age of big data and metrics for everything, here’s a guy embarking on a billion-dollar-plus development based on gut instincts and anecdotal evidence. And it’s this weirdly old-school quality, more than the eye candy, that makes me think Dominotown could be the first credible piece of twenty-first-century urbanism on either side of the East River.