Emily Badger reports for The Washington Post: An economic defense of old buildings.

Jane Jacobs, a woman akin to the patron saint of urban planners, first argued 50 years ago that healthy neighborhoods need old buildings. Aging, creaky, faded, “charming” buildings. Retired couples and young families need the cheap rent they promise. Small businesses need the cramped offices they contain. Streets need the diversity created not just when different people coexist, but when buildings of varying vintage do, too.

“Cities need old buildings so badly,” Jacobs wrote in her classic “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” “it is probably impossible for vigorous streets and districts to grow without them.”

Ever since, this idea — based on the intuition of a woman who was surveying her own New York Greenwich Village neighborhood — has been received wisdom among planners and urban theorists. But what happens when we look at the data?

The National Trust for Historic Preservation has tried to do just this, leveraging open property-parcel data in three cities to analyze the connection between the kinds of places Jacobs was describing and the numbers that economists and businesses would care about: jobs per square foot, the share of small businesses to big chains, the number of minority- and women-owned businesses.

The novel geospatial analysis, drawn from the District of Columbia, Seattle and San Francisco, suggests that older, smaller buildings do matter to a city’s economy and a neighborhood’s commercial life beyond the allure of affordable fixer-uppers. In Seattle, the report found one-third more jobs per commercial square foot in parts of town with a variety of older, smaller buildings mixed in. In Seattle, it found more than twice the rate of women and minority-owned businesses. In the District, it found a higher share of non-chain businesses.

The findings don’t necessarily mean we should save all old buildings from demolition, or even that one old building is better than one new one. But they give preservationists (and Jane Jacobs enthusiasts) new data in fierce development debates over how rapidly changing and relatively older cities like Washington should grow.

“For a long time, preservationists have been making the the cultural argument that these places feed our soul, and they connect us to our past,” says Stephanie Meeks, the president and CEO of the National Trust of the National Trust. “But this is the first time we’ve had empirical data to show that these places perform better economically and on many livability factors, as well.”

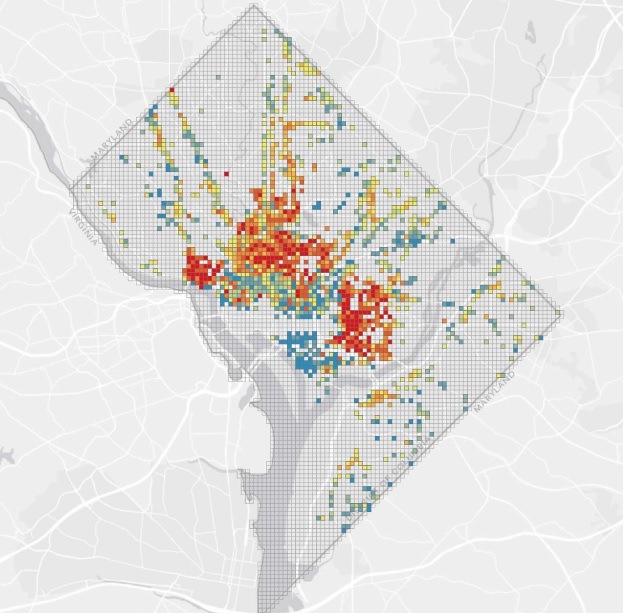

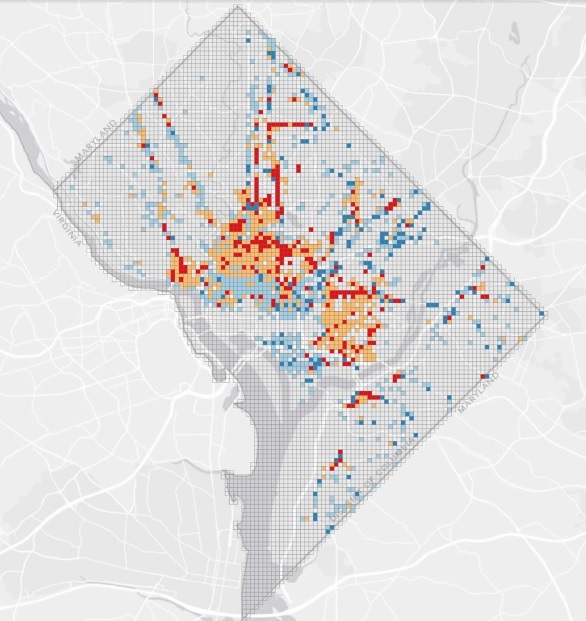

The report divided each city into a grid of 200-by-200-meter squares to allow comparison across neighborhoods (city blocks tend to be different sizes even across the same city, making that unit a poor measure). This is Washington, with its main commercial and mixed-use neighborhoods highlighted:

The Jacobsian quality of each grid square was measured by a “character score” combining three factors from county assessor data: the median building age there, the diversity of building ages (as a standard deviation), and the “granularity” of many small buildings versus a few large ones (think H Street instead of NoMa).

“If you‘re walking for 30 seconds down a street, how many interesting things do you pass?” asks Michael Powe, the lead researcher on the project with the trust’sPreservation Green Lab. “That’s a good measure of granularity.”

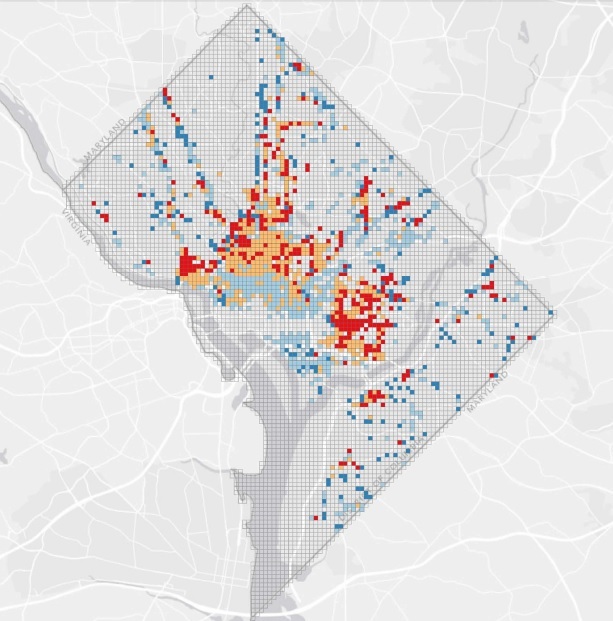

The report then compared the results to more than 40 metrics of economic and social life, accounting for differences across neighborhoods in median income, transit accessibility and private reinvestment. The trust looked at concentrations of social activity through cellphone use, at businesses per 1,000 square feet of commercial space, at population density and walkability scores. This is the map of small businesses in Washington:

And here are new businesses launched in 2012:

The trust acknowledges that these are sophisticated correlations at best; it’s hard to say that old buildings cause small and minority-owned businesses to open shop, or that theycause twentysomethings to congregate on Friday nights. Still, smaller, older buildings don’t lend themselves well to formulaic chain stores, making them a good home for other kinds of businesses that don’t then have to compete for rent with Starbucks and Chili’s. This means that the barriers to entry are lower on a strip like H Street.

Neighborhoods with many small shops and restaurants side by side are also more conducive to foot traffic and the kind of unanticipated business that’s created when you walk to a restaurant on Barracks Row in Capitol Hill and later wind up at a bar next door.

The trust argues that these qualities inherent in older, smaller-scale building stock keep cities affordable for local businesses and lower-income renters, although economists like Edward Glaeser have argued precisely the opposite: that preservationists who oppose new development restrict the supply of new housing that might drive prices down.

“The idea that building new is going to lead to greater affordability has been the standard economic model of supply and demand,” Powe says, “and that may hold true in the aggregate at the end of the day. But it’s very hard to build new affordable housing, and this is a great natural stock of affordable stuff.”

For the whole report click here.