Lisa Santoro reports for Curbed New York.

Banking and commerce are integral to the city’s livelihood, so it’s no wonder that New York City’s banking institutions are designed to look important. This is certainly the case with Central Savings Bank, which stands out even among the noteworthy classical structures that are its neighbors. The building is easily accessible to the public and warrants a closer look.

The Central Savings Bank (currently Apple Bank), located at 2100-2108 Broadway at West 73rd Street, was built between 1926 and 1928 by the architecture firm of York & Sawyer. The bank had been founded in 1859 and was originally known as The German Savings Bank in the City of New York, with its first location inside the Cooper Union building. Just five years later, in 1864, the bank would move a bit uptown to Fourth Avenue and 14th Street, eventually occupying a new bank building that was constructed in 1872. Decades later, during World War I, the bank changed its name to “Central Savings Bank.” Though the name change may have been due to anti-German sentiment, the bank continued to flourish and the trustees banked (sorry) on the Upper West Side’s business and residential development and chose to open an uptown branch.

York and Sawyer was an obvious choice for the new building. In addition to both working for the prolific firm of McKim, Mead and White, York and Sawyer were experienced in designing other noteworthy banking institutions, such as the Federal Reserve Bank of New York on Liberty Street and the Bowery Savings Bank on 42nd Street. The Central Savings Bank commission would be especially stately given its unique location atop a trapezoidal lot adjacent to Verdi Square. With the latitude to design a building free from the confines of adjacent structures, and complemented by nearby open space, the designers were able to create a unique, iconic structure.

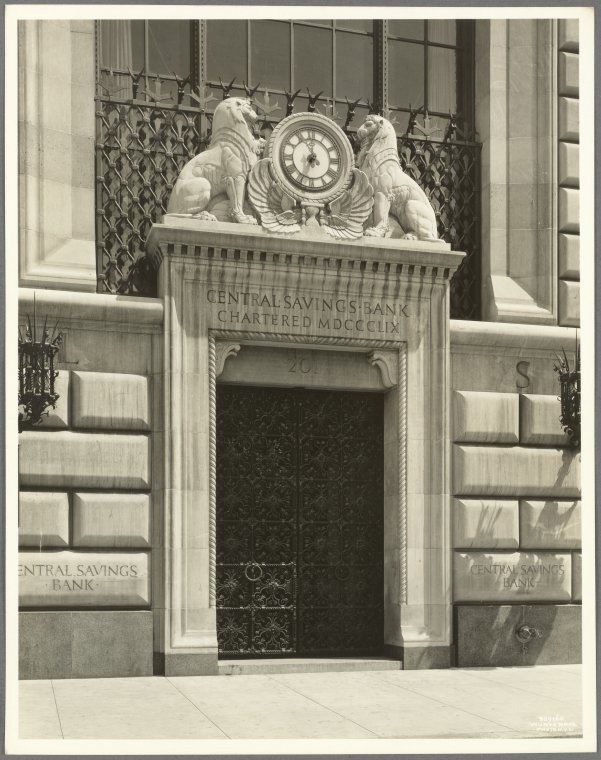

That structure was a six-story freestanding building designed in the style of an Italian Renaissance palazzo. Constructed of rusticated limestone, the building was adorned with decoration that would in fact be very fitting for a palazzo. This included the two lions surrounding the clock above the main entrance, cartouches featuring the heads of classical figures and shields containing the caduceus motif and two snakes ensnarled around a staff—which has become the modern symbol of commerce and negotiation. In addition, the exterior features stunning wrought iron doors, gates, grilles and lanterns designed by Samuel Yellin, considered the country’s master iron craftsman during the 1920s. The building is still not as highly decorated and elaborate as its Parisian-inspired neighbors to the south, the Ansonia and the Dorilton, but is instead serious and refined.

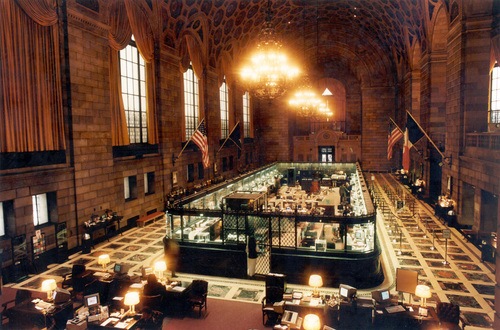

The building stands like an imposing fortress, exuding strength and stability, qualities that very much befit a financial institution. And the building is even more majestic inside. Upon initial entry, the visitor is transported into the cavernous and vaulted main banking hall, in which the building’s tall arched windows provide natural light. The 65-foot coffered ceiling is based on the ceiling of Florence’s Davanzati Palace. The main hall also showcases Yellin’s interior ironwork, specifically the bank screens, grilles, mailboxes and signs. And don’t forget to look down, or you might miss the intricate multi-colored marble floor, which has sustained nearly ninety years of wear.

The bank’s executive offices located on the mezzanine level are also highly stylized. According to Christopher Gray, the offices were “decorated by the Barnet Phillips Company” and “included double-height meeting rooms with large fireplaces flanked by iron torcheres, beamed ceilings, wooden paneling and elaborate faux wall painting with imitation garlands and spirals of fabric.” In order to make some profit from the large building, the upper floors were designed to be rental office space. And although these offices on the upper floors are considered plain and less decorative than the rest of the building, there is elegance in their simple design. These offices feature “solid metal doors with inset panels and an upper section of frosted glass,” brass signboards and “walls wainscoted with marble.”

The Central Savings Bank stands as a monument to commerce, consumerism and finance. Through its design, the building fosters a sense of safety and security—a prime example of how architecture can be emblematic of its building’s purpose and function. The architects sought to create a building in which people would be comfortable investing and depositing their hard-earned money. And what better way to represent strength, stability and success than to have the bank designed in the style of a Renaissance palazzo? The words spoken at the bank’s 75th anniversary in 1934 still ring true: “The Central Savings Bank is housed in truly a noble building, its lofty interior and its massive exterior typifying all that the Bank has represented in the past—all that the future may bring to us in the way of health and happiness.”