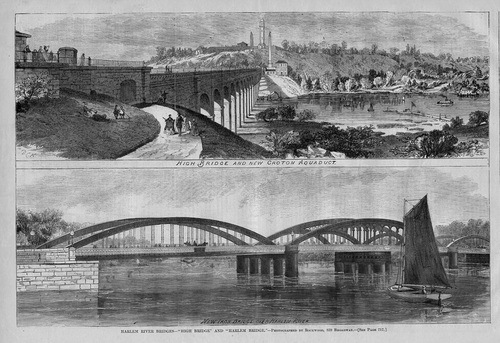

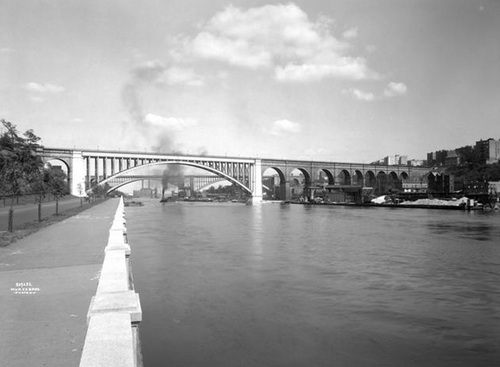

[The High Bridge and Harlem Bridge, pictured in a 1867 issue of Harper’s Weekly]

The Bronx side of the Harlem River in High Bridge is a park-starved neighborhood, dominated by concrete expressways and desolate industrial lots, but soon a long-closed link will reconnect the area to greener pastures on the Manhattan side of the river. Construction crews are working to restore the 165-year-old High Bridge, the great architectural and civil engineering marvel of the Harlem River Valley that’s been closed and crumbling since the 1970s, cutting off the South Bronx from Highbridge Park. Officials broke ground on a $61 million restoration earlier this year, and by next summer the landmark will reopen to the public, bringing with it a renewed interest in the waterfront area.

When the bridge first opened in 1848, 35 years before the Brooklyn Bridge, it was hailed as a marvel of civil engineering. Designed by engineer John B. Jervis, who worked on the Erie Canal, the bridge rises 138-feet tall and stretches 1,450-feet long, making it the longest bridge in the United States when it was completed.

The water traveled about 41 miles from the Croton River in Westchester across the High Bridge into Manhattan, moving entirely by gravity through pipes that were constructed below the bridge’s walkway. The iconic fortified-looking High Bridge Water Tower, which dominates the adjacent Highbridge Park and overlooks the Manhattan end of the great span, was completed in 1872. It served to pump water uptown to residents living at the higher elevations of the island.

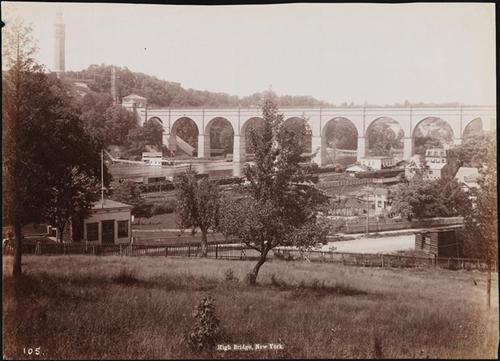

[Circa 1905. Photo via MCNY]

At the time of the bridge’s construction, Mayor Robert H. Morris predicted to New Yorkers that this nineteenth century descendant of Roman greatness would “endure for ages, would bear record to these ages, however distant, of a race of men who were content to incur present burdens for the benefit of a posterity they could never know.” Indeed, the High Bridge became the crown jewel of the Old Croton Aqueduct System providing New York City with its first successful access to a reliable supply of fresh water and marked the beginning of a more sophisticated and progressive city.

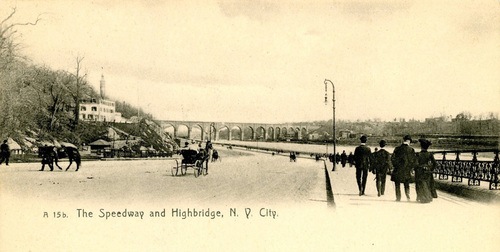

[Circa 1906]

The High Bridge, however, was much more than simply a piece of public infrastructure. It also was beloved for transforming the area into a favorite destination of Manhattanities seeking an escape from the crowds and concrete of downtown, and it served as a vital crossing between the Bronx and Manhattan for nearby residents. None other than Edgar Allen Poe found the pedestrian bridge a favorite route to get across the river to and from his Bronx cottage.

Throughout the mid-nineteenth to early twentieth centuries, the High Bridge and Harlem River waterfront were two of northern New York City’s great attractions. People enjoyed the nearby restaurants and Fort George Amusement Park atop the bluffs of Highbridge Park, and regattas drew crowds of spectators, as did the riverside walkway and carriage path, which later became the Harlem River Drive. In 1899, Jesse Lynch Williams of Scribner’s Magazine wrote: “There is a different feeling in the air up along this best-known end of the city’s water-front. The small, unimportant looking winding river, long distance views, wooded hills, green terraces, and even the great solid masonry of High Bridge…help to make you feel the spirit of freedom and outdoors and relaxation. This is the tired city’s playground.”

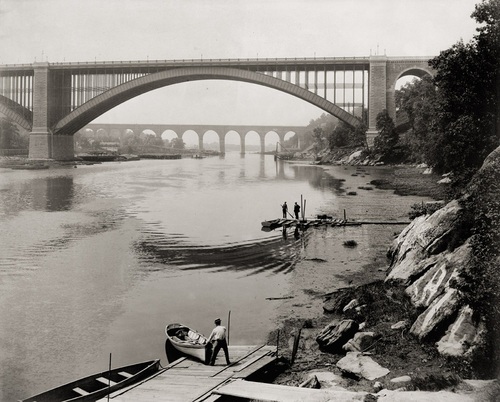

[Famed photographer William Henry Jackson, known for his images of the American west, documented the High Bridge in the 1890s]

Writers and artists made the trip uptown to record their interpretations of the valley’s sights and sounds, and the High Bridge even made a cameo in Edith Wharton’s 1913 novel, Custom of the Country, in which the heroine, Undine Spragg, rides uptown to attend a dinner party.

[The High Bridge in 1929, with the new steel span. Photo via MCNY]

Despite the continued popularity of the High Bridge as a travel destination, by the 1910s concern had grown about the danger its piers posed to river traffic. Its mighty granite arches were viewed by the Army Corps of Engineers as a serious impediment to shipping. Calls were made to remove some of the center piers, then they decided to petition for the complete demolition of the bridge. After a long and contested public debate, a compromise was reached in 1927, and the city approved the removal of the five center arches. A single steel arch with a 360-foot wide lateral clearance replaced the masonry arches. When the bridge reopened with its altered appearance in 1928, the Times wrote: “High Bridge, decked with flags and echoing with speeches, was opened to traffic again on Saturday. But what strange traffic! No other bridge about the city carries any just like it: waters from the Old Croton Aqueduct, pedestrians crossing to the Bronx, promenaders taking advantage on a summer’s evening, as they have for almost a century, of the cool breezes and fine prospect, couples arm in arm. No clanking cars, no honking motors! . . . As the steel span symbolizes the future, so the old arches stand as a link with the past.”

[Overgrown High Bridge in 2009. Photo by Barry Yanowitz/Curbed Flickr pool]

Things started to go south in the mid-twentieth century. Increased industrial activity had polluted the river, and the construction of the Major Deegan Expressway and Harlem River Drive all but eliminated public enjoyment of the waterfront by the 1950s. The following decades saw increased rates of poverty, unemployment and crime in northern Manhattan and the southern Bronx. The decline in public consciousness and interest in the High Bridge was not helped by the fact that the great span itself ceased to provide fresh water to the city by 1958; new supplies of water from the development and expansion of the Catskill and Delaware aqueduct systems replaced the Old Croton system. The city lacked both the funds and interest to maintain and police it, so access to the pedestrian walkway was closed in 1960, and the span itself was closed in 1970, the same year the bridge was landmarked. In 1972, the bridge and water tower were both placed on the National Register of Historic Places, but the bridge continued to decay, and arsonists destroyed part of the Water Tower in 1984.

[View of the High Bridge from Highbridge Park in 2012. Photo by Duane Bailey-Castro]

The 21st century brought a new era for the bridge. In 2001, the High Bridge Coalition was founded to focus on the rehabilitation and reopening of New York City’s oldest bridge. The group also sought to cleanup and expand neighboring parks and improve public access to the Harlem River waterfront. The coalition formed partnerships with the Parks Department, which owns the bridge, and the Department of Transportation, which conducted early structural assessments of the span as well as offered preliminary estimates of the cost to restore it. The city’s political leaders began to lend their support, and in 2001, the 130-acre Highbridge Park was renovated for $739,000. The first federal funds for restoration were secured in 2006, and the following year, Mayor Bloomberg committed to the restoration of the High Bridge as part of PlaNYC.

[Photo by Duane Bailey-Castro]

In January 2013, ground finally broke on the long awaited restoration, which includes structural improvements, dust and soot removal, the repainting of the steel arch, the resetting of its brick deck, safety fencing, and new lights for evening use. A member of the Parks Department recently told the Times that the bridge is “really the centerpiece of the Harlem River corridor” and exemplifies how much the city is committed to revitalizing the waterway and surrounding neighborhoods.