Paul Gunther writes on Architizer.

Grand Central Terminal. Image via The Daily Beast.

Just days ago, New York Senator Chuck Schumer characterized preservationists as “those people [who] would see the city die a slow death.” With an eye on the shifts under way in New York politics, it is time to put to rest this false dichotomy between landmark preservation and economic progress. The Forum for Urban Design recently published an amalgam of alternative public policy ideas entitled “Next New York” (a handy must-read for any civic-minded design professional or associated gadfly). One of the included essays calls for the elimination of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, placing its duties under the umbrella of the City Planning Commission. This argument is based on the idea that the City Planning Commission makes objective, politics-free decisions, while the decision-making process of the Landmarks Planning Commission is “opaque” and “capricious.” The essay cautions against “landmarking” away the economic vitality of New York City.”

The Landmarks Preservation Commission has recently given permission to SHoP Architects to build a 1,350-foot residential tower at 107 West 57th Street in Manhattan.

In light of these criticisms, it is necessary to check the facts. For better or worse, the tension between Planning and Landmarks has evolved as the best defense against the huge scale developments that seem most often to replace rather than complement. Change is, and always will be, an aspect of any vibrant and healthy city, but today that reality seems to translate directly to vast height and increased density; until “new” can include greater contextual deference, this tension will—and should—endure. A healthy city is not a monoculture. Preservation, development, and prosperity have always been natural bedfellows: without the fabled landscapes of Central Park and the Upper East and West Sides, one could not sell $100 million apartments along 57th Street. Even in the absence of design excellence, the property can rely on views, proximity and a historic address. “Landmarking” raises the worth of surrounding areas exponentially—the numbers don’t lie. It’s ironic that those who sought to destroy Grand Central Terminal 40 years ago, calling its preservation an impediment to progress, are being quoted anew, when in fact the preservation of Grand Central may be the foremost force behind the push for increased density.

Philip Johnson, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Bess Myerson, and former Mayor Ed Koch on Jan. 30, 1975 as they leave New York’s Grand Central after holding a news conference for the “Committee to Save Grand Central Station.”

Image via Municipal Art Society.

Additionally, landmarks rank as the top driver of what is by far the biggest growth engine in New York: tourism. According to Crain’s New York, in the last decade, the tourism sector has expanded by 41.5%, outpacing all other categories and “more than compensating for job losses elsewhere including manufacturing.” These jobs require a wide variety of skills, making them a perfect match for modern urban demographics. Plus, positive perceptions of a travel destination can mean an increase in design and construction opportunities—in just the last 5 years, hotel space in New York City increased by 23.7%. (Even as hotel room inventory increased, rooms stayed full—in May of 2013, 91.9% of NYC hotel rooms were in use.)

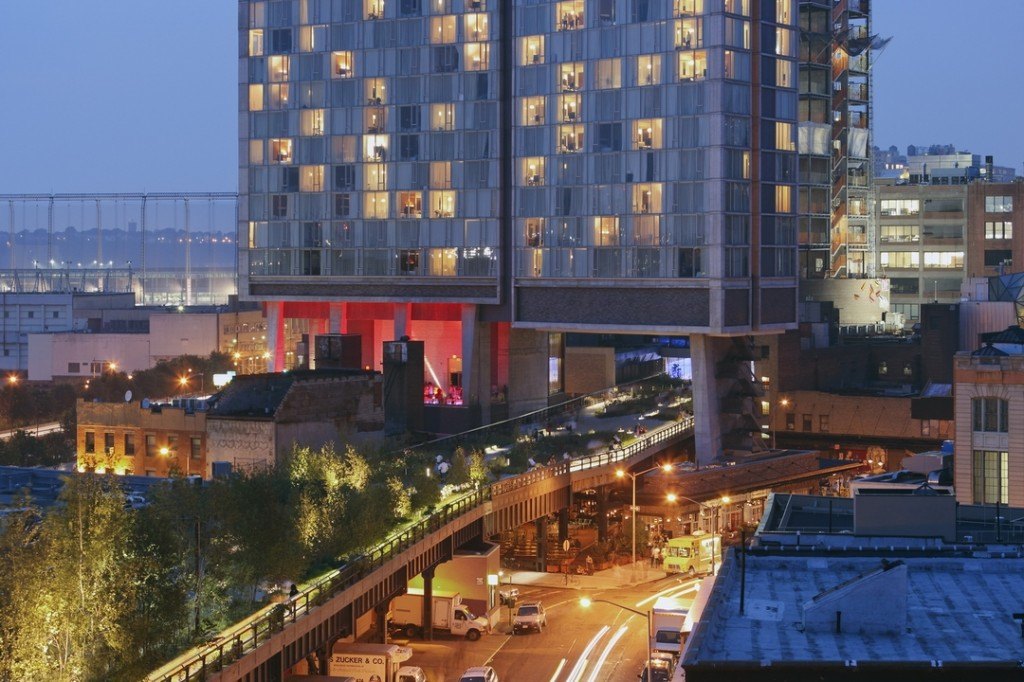

The High Line, a new tourist attraction, and the adjacent Standard Hotel.

What visitors seek, above all, are landmarks. Of the top 10 New York City tourist destinations, for example, nine are landmarks; tourists come for the city that is, its image bright in the collective imagination. Any who see preservation as a threat to the city’s momentum should take a cold hard look at the economic facts. Some may describe such reliance on the past as doomed to decline, but it is undeniable that the endurance of beloved landmarks leads directly to economic well-being. If the dollars and jobs generated by tourism are judged as inferior to those generated by new construction, then New York risks becoming a Shanghai wannabe, a hub of 9-to-5 banality. The Chinese are now reconsidering the abnegation of their cultural past; New York must never follow suit. Preservation does not obviate construction or development; a mere five percent of the five boroughs’ real estate falls under Landmarks’ protection. That translates into a minute 27,000 properties, including historic districts. While the incoming mayor and his senior staff should reform the designation and enforcement processes of the Landmarks Preservation Commission by increasing transparency, fairness, client ease, and efficiency, the robust preservation movement of New York City must continue for the sake of prosperity, strong communities, and regional identity—an identity visitors pay to experience.