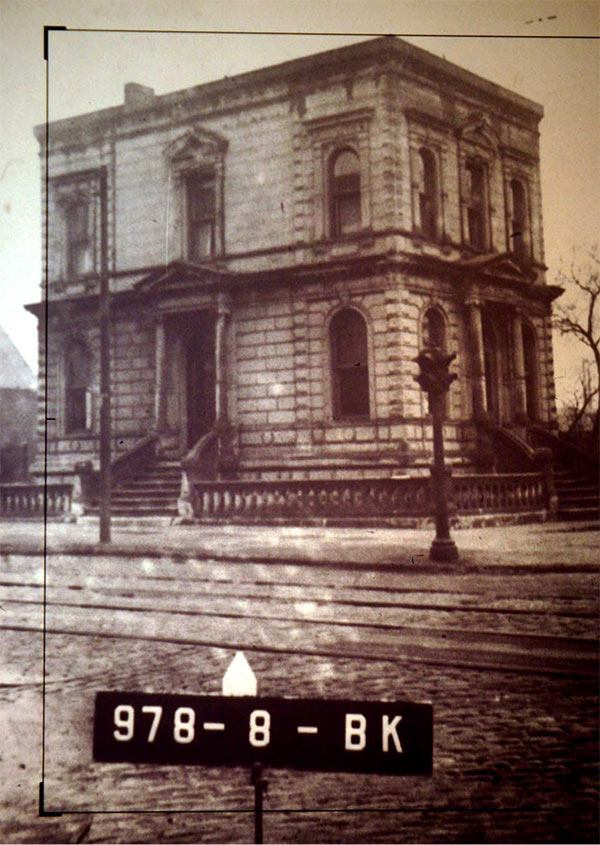

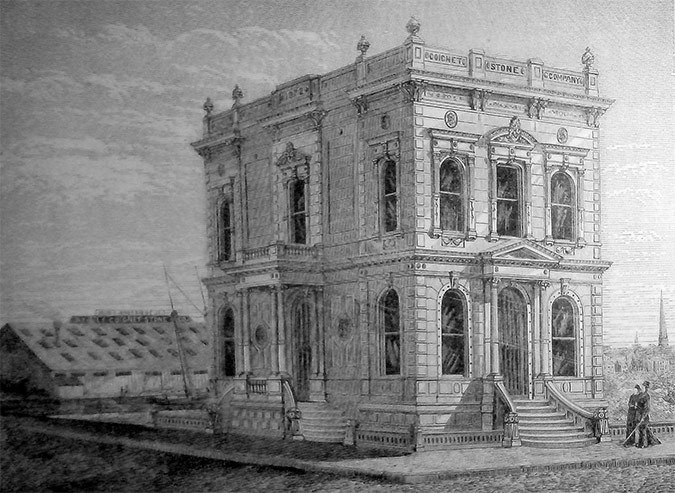

American concrete begins in Brooklyn. The New York and Long Island Stone Contracting Company, formed in 1869, was the first U.S. company to produce concrete, and its headquarters, located at 3rd Avenue and 3rd Street in Gowanus, is the earliest concrete building in New York City, dating from 1872.

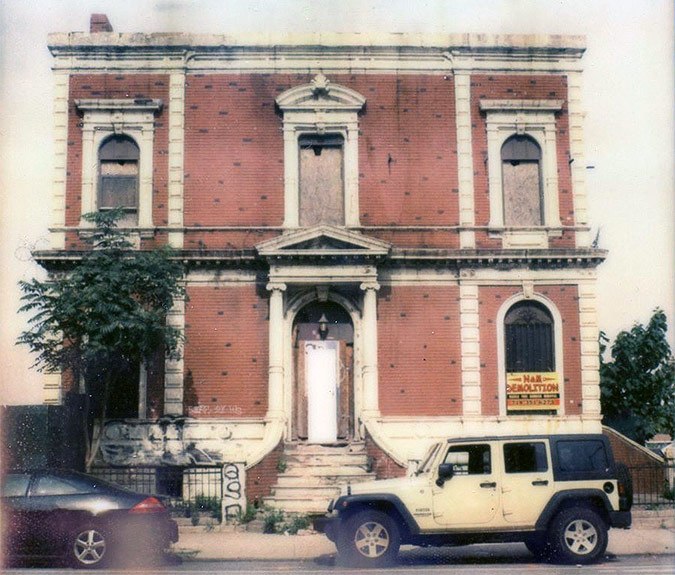

The Coignet Building—as it is colloquially known, for the name of its early concrete product, coignet stone—has become one of the most watched New York City landmarks in peril. Designated in 2006—likely sparing it from demolition—the building stood alone for years as brownfield remediation plans for the Whole Foods Brooklyn site dragged on. It was a frequent target for photographers looking for a slice of Detroit-like decay in the otherwise booming borough, and with the Whole Foods complex now complete, the Coignet Building is all the more prominent as a near ruin penned against the gleaming new grocery.

Whole Foods is bound by a 2011 covenant with the building’s owner (who formerly owned the entire site where the grocery now sits) to restore the building’s exterior. Those who have been closely watching the building’s decay had expected any plans for its restoration to go to a hearing before the Landmarks Preservation Commission. However, with no fanfare, the New York Department of Buildings in early February issued permits for work on the site, following Landmarks’ 2013 issuing of a staff-level certificate of no effect for the proposed work, which means that there will be no public comment.

News of the Coignet Building’s restoration should be welcome. However, the building has arguably suffered through attempted demolition by neglect in the past decade, and the Landmarks permit allows for “removing and replacing in-kind severely deteriorated cast stone units” including the “cornice, quoins, columns, pilasters, window surrounds, door surrounds, sills, and the entryway pediments, architraves and friezes”—i.e. much of the exposed original coignet stone on the building whose decay is directly attributable to this neglect.

The building is of extreme historical importance for its role in materials history—it is the Genesis 1:1 of American concrete production. The Coignet Building’s significance is indisputably tied to the material from which it is constructed, the artificial stone produced at the concrete manufacturing yards located behind it, where Whole Foods now sits. Besides the Coignet Building, only three other known locations across New York feature the company’s concrete: the Cleft Ridge Span in Prospect Park, select locations in the arches of St. Patrick Cathedral in Midtown, and three surviving houses on Clinton Avenue in Brooklyn. Any replacement of the original material at the Coignet Building should be held to an extraordinary high standard.

Kate Daly, the executive director of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, and one of the researchers responsible for the discovery of the building’s significance and subsequent designation, maintains that alarm is not warranted, as Landmarks plans to work closely with the architects to evaluate the condition of the original material. However, an earlier iteration of drawings submitted to Landmarks by BL Architects—a firm with no consequential technical preservation experience in New York City—clearly indicates much of the building for replacement based only on a visual inspection. Though one hopes that Landmarks staff will hold the architects’ feet to the fire on the matter, as Daly promises, it is extremely disappointing that they will not be required to do so in public before the commission, or to submit a more detailed analysis of existing conditions as a condition for the building permit.

The Landmarks approval conditions stipulate that the architects submit material samples for replacement in kind for concrete units that are deteriorated beyond repair. This issue is fraught with enormous questions of authenticity—should replacement simply match the appearance of the coignet stone, or does replacement in kind mean using the original concrete production process, presumably different from modern methods of producing cast stone? Since coignet stone belonged to a wider category of substitute stone denounced in the nineteenth century by Ruskinian adherents as sham imitations of stone, this question goes to the very nature of the material. (Indeed, Coignet company literature touted that its “artificial stone” was superior to nature’s own product.)

The lack of care for the building (and the awkward abutment of the new Whole Foods complex around it) are ironic given the homilies to the sustainability inside the grocery store: prominently placed signs tout that the building is made from the reclaimed bricks and salvaged boardwalks destroyed in Sandy, and that it is located on a “remediated brownfield site to protect the environment” and “reduce blight.”

Restoring the building in the most careful fashion likely would cost Whole Foods the least, as the building is eligible for historic tax credits worth up to 40 percent of project costs. This is a path that, to my knowledge, Whole Foods has chosen not to pursue, costing the company hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Indeed, the building’s apparent decay may be illusory. The exposed coignet stone is covered in a later stucco coating that easily flakes off to the touch, and, besides cracks in the underlying stone, may actually be in reasonable shape. Having closely watched the building crumble, we must even more closely watch its nominal restoration.